Look at any world map and find Prudhoe Bay in Northern Alaska or the southernmost city in the world, Ushuaia, Argentina. If you try to follow your finger from one of these extremes to the other following roads, you will ultimately come at a stop upon encountering the Darién Gap in Panama. Still today, the dense, wild forests dominating the landscape of the Darién Gap are the only thing preventing a continuous road across the Americas. And hopefully the pristine habitat remains that way, for many endemic species and indigenous communities depend on it.

I first heard of the Darién two years ago when I came to Panama with McGill University, and it was introduced to us as the forbidden province. We visited the 8 other provinces, flew to remote islands and drove through treacherous dirt roads to reach isolated communities, but under no circumstances were we allowed to enter the Darién. Aside from being known for its untarnished biodiversity, the Darién's reputation is clouded by its numerous kidnappings, assassinations, and the presence of Colombian guerrillas patrolling the Panama-Colombia border. The Lonely Planet guide even has a "Surviving the Darién" section. While these dangers are very real, they are often blown out of proportion, and any mention of visiting the Darién is often followed by alarmed gasps and warnings. But the fish I study are there calling for me and into the Darién I must go.

So how do you prepare for a 10-day trip in the Darién? First, a long day at the grocery store to stock up on food for 10 days. Getting my head chopped off by machete-wielding guerrilla is fine, but I don't want to die without a few hojaldres in my belly. Second, the trucks are then packed to their maximum capacity until all passengers are drowning in field gear such as solar panels, fish nets, car batteries, formalin, etc. Finally, the frontier police grants us our permits and we are ready to go.

1 of 2 completely packed trucks. Nikon D700 + 20mm 2.8, 1/250, f/2.8, 400.

The road into the Darién was frequently interrupted with police check points that became longer and longer the further away from the city we were. They would ask for our passports, permits and what business we had in the Darién while eyeing us all suspiciously. Upon encountering the final checkpoint before arriving at our destination, I expected another logistics ritual but after greetings from the officer we were just told "Cuídense.", essentially meaning "Take care of yourselves.". We kept on driving. The road progressively transformed into a mosaic of potholes. The more or less inviting cantinas previously lining the highway became increasingly sporadic. Primeval forest started creeping up on the sides of the road, and even the powerlines were peppered with epiphytes growing on them, perhaps a reminder of nature's dominance in Darién. We eventually reached the end of the road, the little town of Yaviza. This is where we met up with Marín and Martín, two men from the Embera community of Peña Bijagual, our final destination. The only way in is through the large Río Chucunaque. As the sun was setting, they helped us unload everything out of the trucks and into two huge dug-out canoes. And then, off we went.

The 2-hour long starlit canoe ride on the Chucunaque was probably one of the most memorable experiences I've ever had. The only sounds heard were the occasional eerie animal calls, the water flowing past us and the gentle humming of the motors lulling us to sleep. Silhouetted trees lined the river banks, growing to colossal sizes as we approached them. When the moonlight was not enough for guidance, Marín, sitting in front of the canoe turned on the flashlight, revealing dozens of caiman eyes poking out of the water.

8-second exposure of a pitch black scene save for the few flashes from Marín's spotlight. Nikon D700 + 20mm 2.8, 8s, 2.8, 6400.

We finally reach the village and are welcomed by one of the leaders. They lead us to our tents and I fall asleep instantly. I'm not sure if I awoke the next morning because of the sun illuminating the tent, the unbearable heat, the incessant crowing of roosters, or just out of sheer excitement. I stepped out of the tent and finally saw Peña Bijagual, my home for the next week.

When you're out in the field it's hard not to just focus on your research. I was able to relax, meet new people, and also photograph our research. It's hard to find time to document your own fieldwork, but I find it extremely important, especially since you end up with a wealth of great visual aids for future presentations and scientific posters.

The 7 days went by in a flash. Here's a highlight of my stay.

Our tents. Nikon D700 + 20mm 2.8, 1/80, f/13, 800.

Kids in the village. Nikon D700 + 20mm 2.8, 1/160, f/4.0, 400.

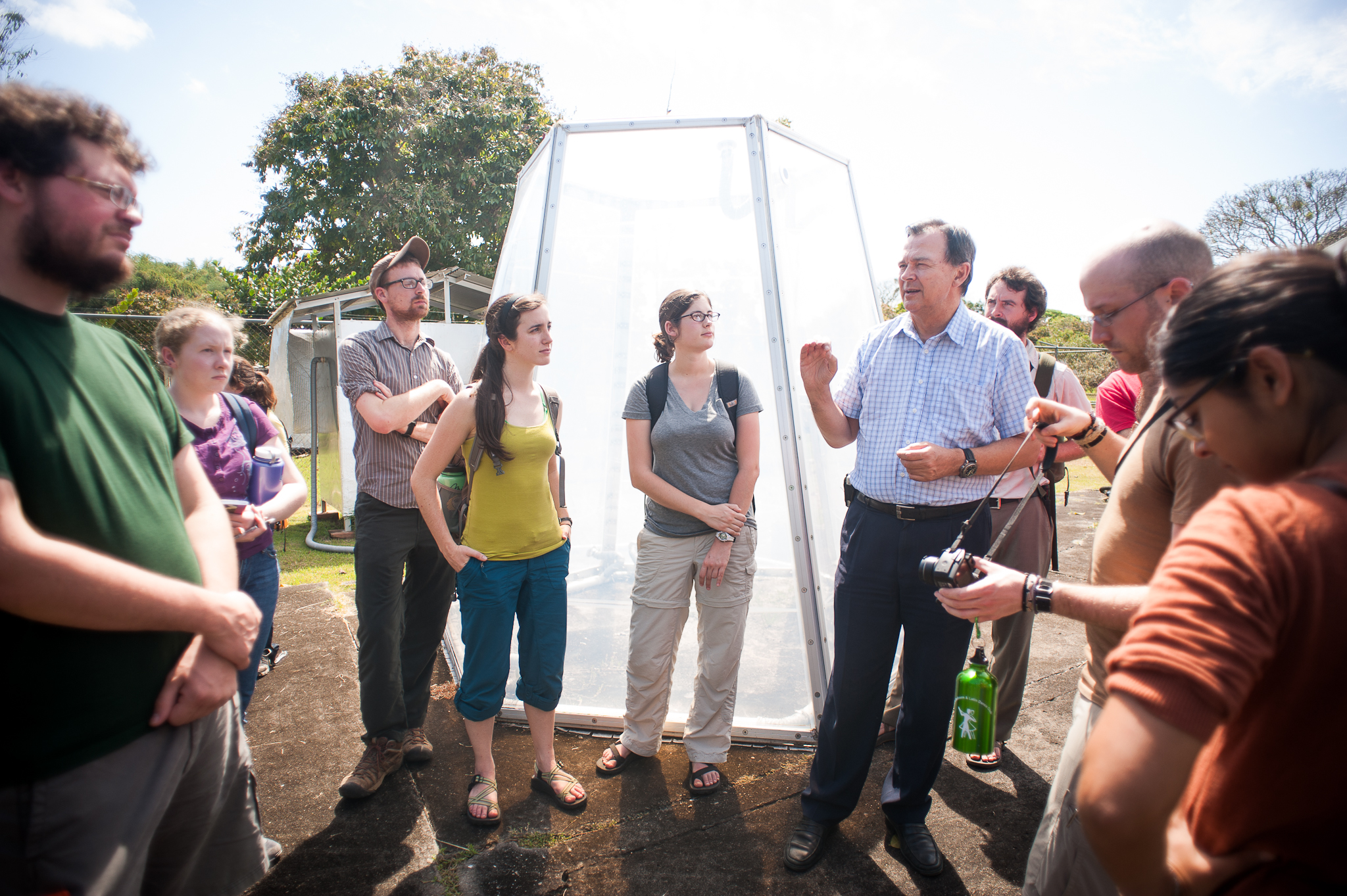

Our field site, a 10-minute hike into the forest. Scientists doing science. Nikon D700 + 20mm 2.8, 1/60, 2.8, 200.

My Emberá bodyguard Marín. Nikon D700 + 50mm 1.4, 1/1250, f/2.2, 1250.

My Emberá bodyguard Marín. Nikon D700 + 50mm 1.4, 1/1250, f/2.2, 1250.

My set-up in the field. I'll explain another time. Nikon D700 + 20mm 2.8, 1/160, f/2.8, 200.

Newlyweds Diana & Luis with us in the field. Nikon D700 + 20mm 2.8, 1/1200, f/2.8, 1250.

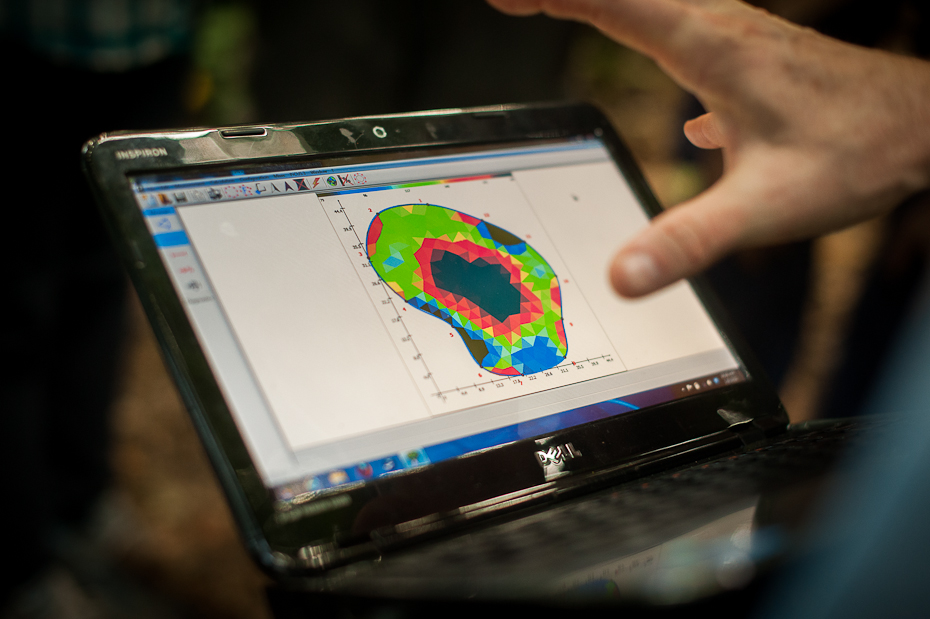

My supervisor Rudiger looking for our electric fish using a fish finder. Nikon D700 + 50mm 1.4, 1/400, f/2.2, 1250.

Fieldwork is fun. Nikon D700 + 50mm 1.4, 1/400, f/2.2, 1250.

As you brave on, the crescendo of car horns indicates that you are near the climax. You’ve reached The Turn, and you’re now fully committed to the Circle of Death. If you’re in a bus, this is the moment where you might feel suspended in mid-air; the bus spins, stands at a 45 degree angle on two wheels. At this very moment, new tourists in the bus are immediately given away - not by their sun burns, flip flops, “Panama” hats (which are neither made, nor really worn by Panamanians), loud voices, travel guides, sunglasses, shorts, backpacks or their pronunciation of the country they’re in (Panamaaahhww), but by their inevitable fall.

As you brave on, the crescendo of car horns indicates that you are near the climax. You’ve reached The Turn, and you’re now fully committed to the Circle of Death. If you’re in a bus, this is the moment where you might feel suspended in mid-air; the bus spins, stands at a 45 degree angle on two wheels. At this very moment, new tourists in the bus are immediately given away - not by their sun burns, flip flops, “Panama” hats (which are neither made, nor really worn by Panamanians), loud voices, travel guides, sunglasses, shorts, backpacks or their pronunciation of the country they’re in (Panamaaahhww), but by their inevitable fall. During The Turn, you dare to peek outside the window, looking up to the sun for hope. Unfortunately, you only encounter a giant “INFLAMABLE - PELIGROSO” stamped on a mammoth tank truck zooming past you. You think, perhaps, to look ahead for the light at the end of the tunnel. Oh but do not be so naive darling, you will only see another bus, just millimeters away from yours. You know that a single bump, even a gentle tap, on any 2 vehicles in The Circle will unleash a whirlwind of fury. So you despair. You close your eyes and wait. The Circle of Death has surely won. It will consume its prey shortly.

During The Turn, you dare to peek outside the window, looking up to the sun for hope. Unfortunately, you only encounter a giant “INFLAMABLE - PELIGROSO” stamped on a mammoth tank truck zooming past you. You think, perhaps, to look ahead for the light at the end of the tunnel. Oh but do not be so naive darling, you will only see another bus, just millimeters away from yours. You know that a single bump, even a gentle tap, on any 2 vehicles in The Circle will unleash a whirlwind of fury. So you despair. You close your eyes and wait. The Circle of Death has surely won. It will consume its prey shortly. At this point I must remind you that this is Panama. Turn signals are futile. Checking blind spots is somewhat of a foreign concept. The road is not shared between happy Honda Civics and

At this point I must remind you that this is Panama. Turn signals are futile. Checking blind spots is somewhat of a foreign concept. The road is not shared between happy Honda Civics and  If you hike up Ancon Hill, where a giant Panama flag proudly waves in the wind, a viewpoint looks down on the Circle of Death. From above and at a distance, it seems deceptively innocent. But you know better. You stand there and watch artificial selection in action. The Circle of Death slowly weeds out those who cannot handle Panamanian roads. Perhaps it is a deliberate invention and a necessary evil after all. But The Circle of Death is not something Elton John will be singing about any time soon.

If you hike up Ancon Hill, where a giant Panama flag proudly waves in the wind, a viewpoint looks down on the Circle of Death. From above and at a distance, it seems deceptively innocent. But you know better. You stand there and watch artificial selection in action. The Circle of Death slowly weeds out those who cannot handle Panamanian roads. Perhaps it is a deliberate invention and a necessary evil after all. But The Circle of Death is not something Elton John will be singing about any time soon.

Although it only took Mara a few minutes to trace ours, more intricate and elaborate patterns sometimes require several hours, an exercise in patience for both artist and canvas. When you take into account that many people in the community become fully painted for certain celebrations, you can imagine how laborious the process becomes.

Although it only took Mara a few minutes to trace ours, more intricate and elaborate patterns sometimes require several hours, an exercise in patience for both artist and canvas. When you take into account that many people in the community become fully painted for certain celebrations, you can imagine how laborious the process becomes.

My Emberá bodyguard Marín. Nikon D700 + 50mm 1.4, 1/1250, f/2.2, 1250.

My Emberá bodyguard Marín. Nikon D700 + 50mm 1.4, 1/1250, f/2.2, 1250.